Telling Stories About Clothing

My exhibition at the Museum of Cornish Life worked with their costume collections: exploring gender and telling the tales that clothing revealed. Stories Told in Stitches tracked the items’ life to access stories about clothing – seeing how and what they showed about gender. This amazing opportunity allowed me to put my ideas and plans into action, bring them to life, and see what was involved in the process.

I explored the life story of items relating to costumes to find out how messages about gender identity have changed. I used a theory developed by J. Daybell, K. Heyam, S. Norrhem & E. Severnisson called ‘Gendering Museums’ to achieve this. Researching the individuals involved in each stage of an item’s life meant the item could represent their stories.

Elite women had the resources and wealth to set garments aside in quality condition, rather than ending up as rags from constant reuse and repurposing. The vast majority of collections consist of elite garments. When these garments represent more than the rich white wearer, we access hidden stories, and marginalised groups have a voice.

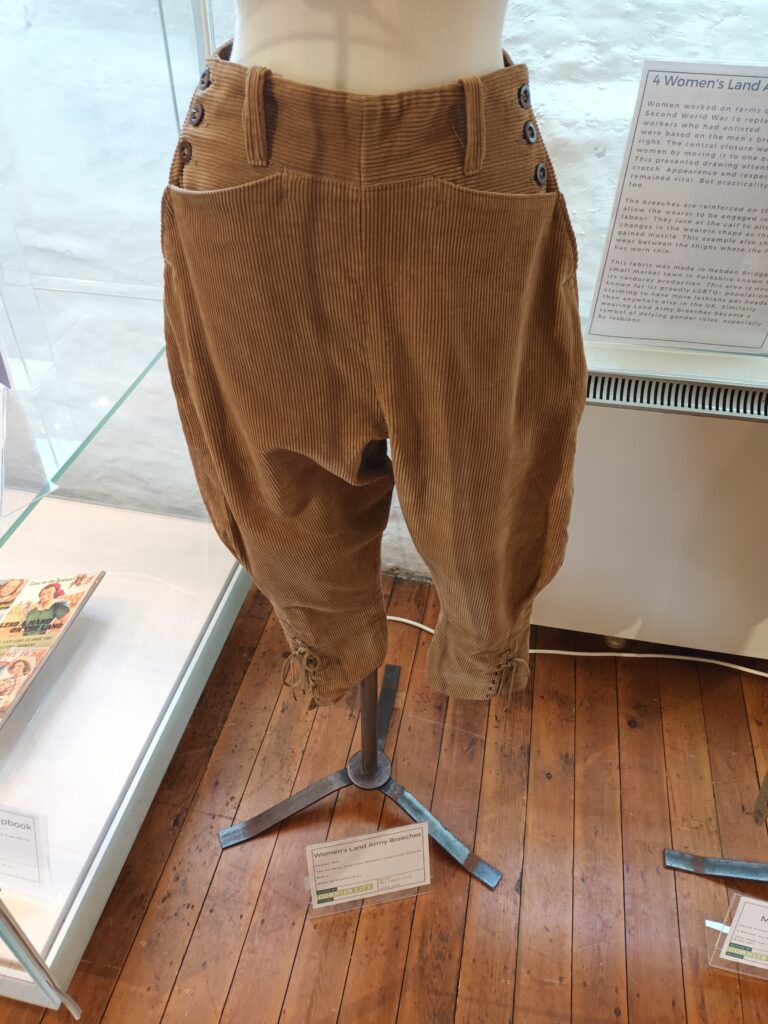

Stories about clothing - Women's Land Army Breeches

As an example, a pair of Women’s Land Army breeches help tell the stories of land girls in the area surrounding the museum (The Lizard) during the Second World War. They also represent those involved in their design, the distribution networks from the base in West Sussex, and their symbolic use after the war as a Lesbian stereotype. This meaning threads through their life – their corduroy was made in Hebden Bridge, known for its claim of having the most lesbians per square foot in the UK.

I loved this approach to the items. It meant my research was influenced by different sectors. I combined specific object research, with items as representations of ideas and museum interpretation theories. For some items, I focused on the stories told as an example of a sort of garment (like the Land Army breeches), whereas for others I explored the personal meaning of its use.

Ethel le Neve

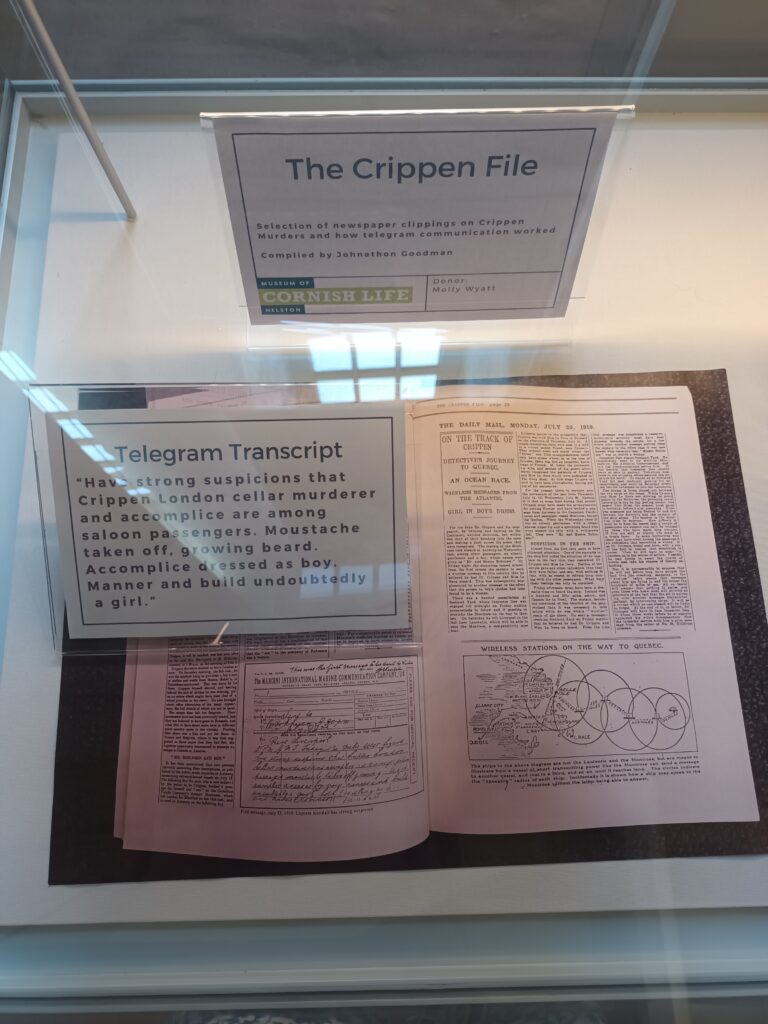

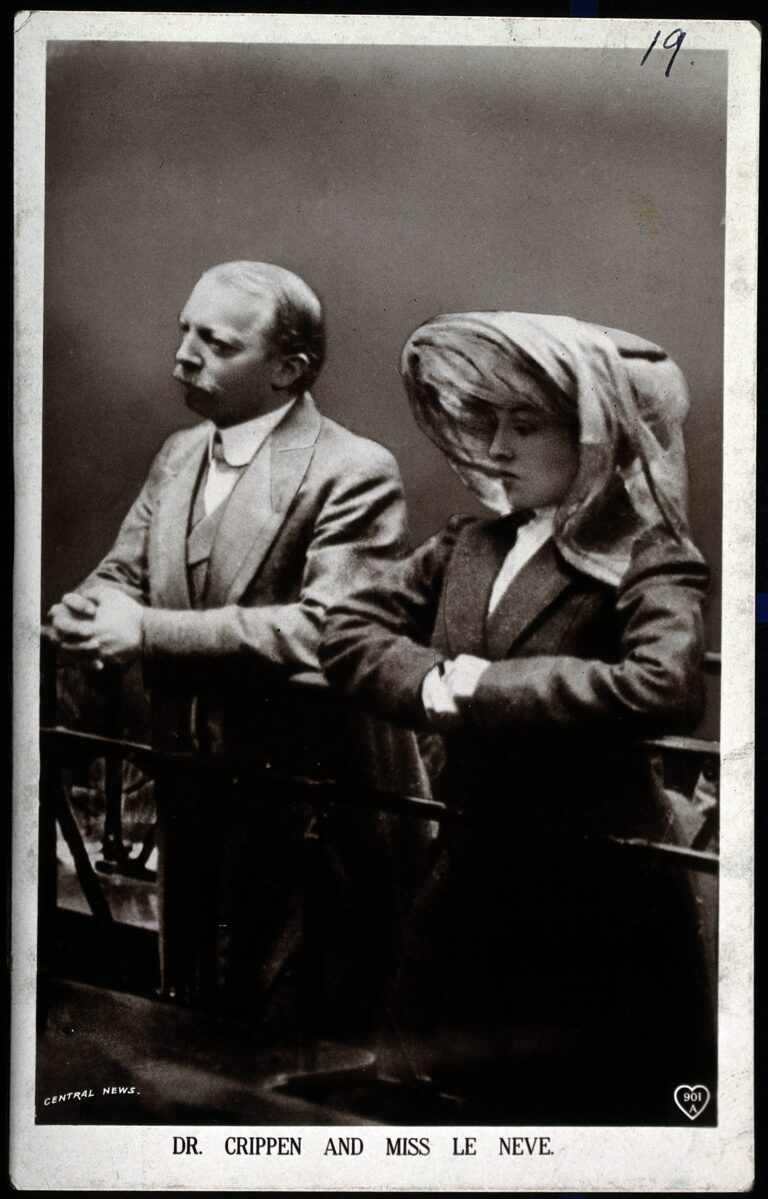

Ethel le Neve was arrested alongside her lover Dr Crippen for the murder of his wife. My story focused on Ethel herself, who claimed ignorance of the murder. This suggests she accompanied Crippen out of loyalty rather than fear of capture. The case is fascinating as it was the first arrest involving the telegram – an invention which was central to Cornish heritage as this was its birthplace.

The SS Montrose left port, in Antwerp, on 20th July 1910 with a copy of a previous day’s newspaper featuring Crippen and Ethel’s photographs. The captain matched these photos to his disguised passengers, despite Crippen’s dyed hair and clean shave. But it was Ethel’s disguise that fascinated me, as she was presented as Crippen’s son, ‘Master Robinson’. Reports claim she was identified by the tight fit of her trousers around her hips and her female mannerisms. A ‘manner and build undoubtedly a girl’. These comments show us that these were defining attributes of femininity at the time. They provide us understanding about gender identification at the time and who was seen as a certain gender.

After her release, Ethel returned to the police and requested the trousers she was arrested in. To me, this means they were a central point of her story and her identity. She cared more about getting to America with her lover than maintaining her presentation as a girl. Her original motivation may have been her loyalty to him. But the fact she requested the trousers back suggests her choice of disguise was important to her.

Stories About Clothing - B. Thomas Mourning Dress

One of the dresses in the Museum of Cornish Life collection is a black mourning dress from c.1900. I built on existing research into its style by the museum’s expert costume team. This tells us about meanings attached to the body at the time – such as valuing a small waist.

The dress had a professional label sewn in, identifying it with “B. Thomas Dressmaker Helston”. I wanted to investigate how it ended up abandoned in Helston’s Guild Hall basement. These clues suggest it never left the town, relatable to local visitors to the museum. This gave me a clear objective – to find why or how it got there!

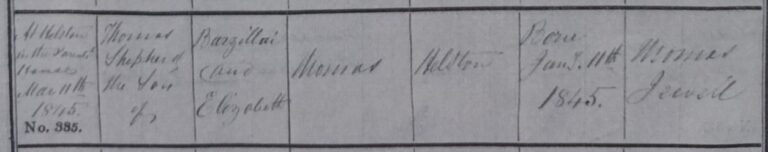

I used Cornish Archives to find out more about B. Thomas and his business. I found out he donated to the workhouse and complained when they commissioned another business for workhouse clothing. This offered insight into B. Thomas’ personality, and when I found the shop’s location, these elements brought the story to life. But they didn’t answer my question.

I did not expect B. Thomas to stand for , but it did help me produce a family tree. A theory soon emerged. His son, Thomas Shepherd Thomas, inherited and ran the shop before dying in 1901. The details suggest an elite wearer but the first advert from female clothing I found was 1907. But it could be for an expert dressmaker’s wife, now his widow, such as Harriet Ann Thomas. Their son Hedley would go on to become the Mayor of Helston in 1909. This could explain how the dress came to be stored and then forgotten in the Guild Hall basement.

Final Thoughts

I loved this experience, so watch out for more articles on my exhibition, exploring more of the stories I uncovered and what I found using the Gendering Museums methodology on a local collection – vastly different to the original examples of the V&A and the Vasa Museum!

Leave a Reply