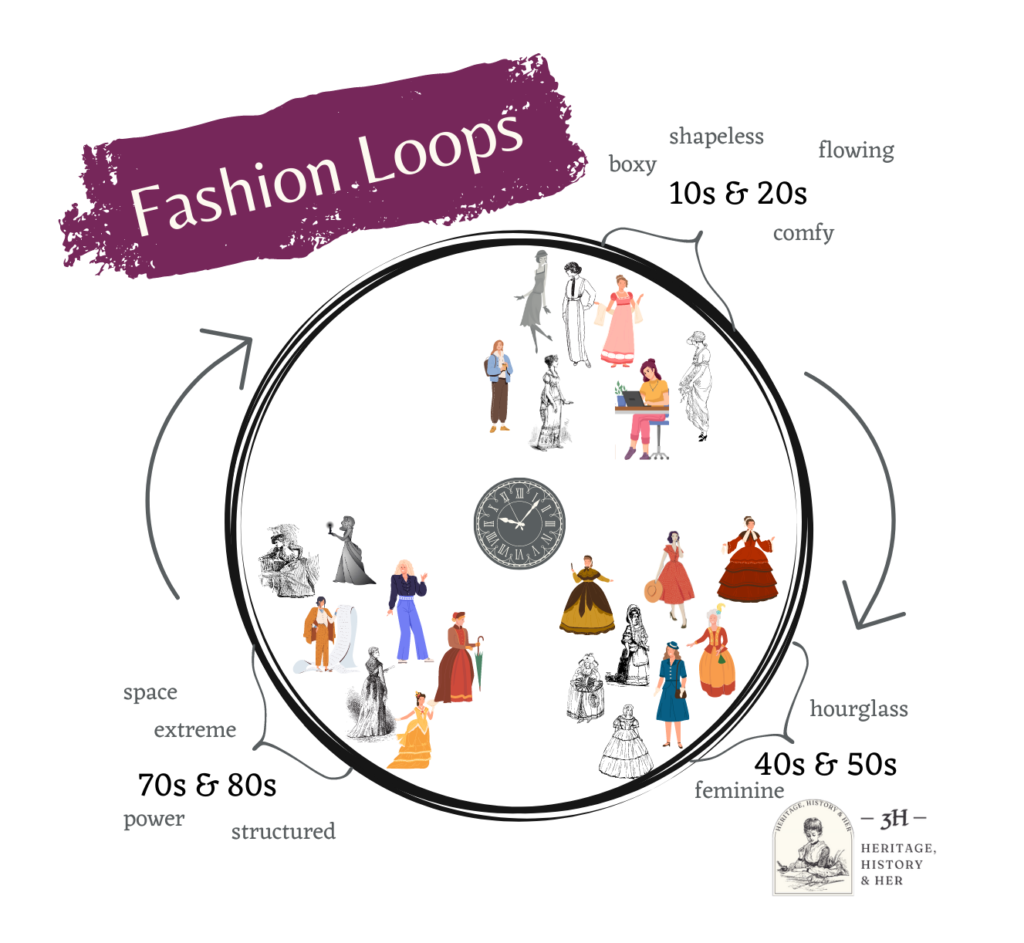

Fashion trends return to the same idea and values almost every 100 years. They may have different presentations but there’s definitely a repetitive fashion loop.

For example, halfway through each century, women returned to a heightened hourglass figure. This was the era of the Victorian crinoline, the ‘New Look’ of the 1950s, and a more rounded shape to petticoats in the 1750s (before the flatter front and back look). Some eras have more than visual similarities but the same meaning behind them.

I find historical clothing fascinating and have done since I was little. I love the gorgeous dresses but also the process and development between styles. Did you know Marie Antoinette and the Regency Era, associated with Jane Austen adaptations, were only 20 years apart?

Like many, I began to understand certain eras in much more detail, and started looking into how they all fit together. What influenced this style to change? One thing that stood out was that almost always a century apart trends return to the same ideas and values. Styles were presented differently but definitely on a repetitive loop.

The 10s & 20s of the previous three centuries have all followed the same trend of abandoning restrictive garments, carried through from the previous decade. This suggests women prioritised comfort. However, comfort was a side effect – not the aim. The aim in each case was to illustrate greater independence and individuality – that women could and would influence change.

The 1810s & 20s saw the Regency Era – flowing, Roman toga-style dresses, forgetting the form and structure that made up previous shapes for more naturalistic shapes. There was even the myth that dresses were made wet to hug the body’s every wrinkle. At the same time we saw the rise of reading for pleasure, with concerns about the damage this, and education, would have on a woman’s prospects in the marriage market.

Napoleon’s attempts to recreate a Roman Empire, following the French Revolution, inspired a return to the clothing of that era and questions of what it meant to be a citizen. Women rejected the enforced structure under dresses associated with the fallen Marie Antoinette and they rejected absolute control with her.

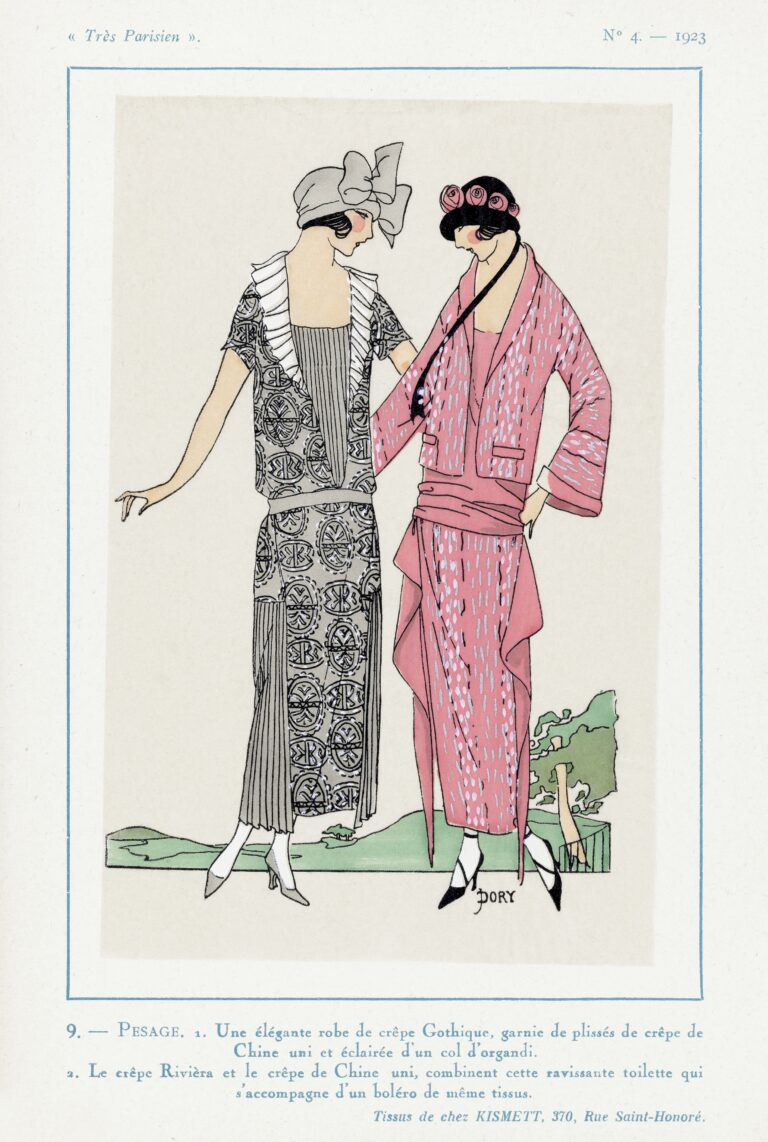

Similarly, most people know the 1920s for flapper dresses – shapeless, shift-like shaped dresses which fall away from the body, suggesting again greater comfort. The 1920s are a clearer example – flappers seemed to reject traditional femininity, instead focusing on entertainment and self-development. They presented themselves as more gender-nonconforming in an attempt to be taken more seriously and judged on more ‘gender-neutral’ terms of worth. In reality, this meant on male terms, maintaining that disadvantage.

Finally, the 2020s saw a shift from tighter-fitting jeans and business wear, to working from home in joggers, and the greater continued rise of sports leisure clothing (wearing gym wear to relax in, not for exercise). Many people re-evaluated their life and lifestyles due to the pandemic and its lockdowns. Many people used the time to gain a new hobby or start their own business. These women took pride in their work, not their appearance – they were outside a traditional workspace and its demands. Working in sports leisure and joggers helped suggest relatability to their audience.

Yet, alongside this came higher expectations for these clothes – women needed to exercise more to meet societal beauty standards that came with these clothes. Like the flappers, greater comfort and self-prioritisation could only be an aim, it was not achievable.

The 70s & 80s were opposite, in style and the loop, to the 10s & 20s. They were highly structured and often the most extreme styles. These are the decades of Marie Antoinette, power shoulders, and the bustle. Each of these represent power plays.

The 1780s saw paniers reach an extreme width. These were cage-like structures on each hip, resembling donkies’ baskets, from where they took their name. Caricature artists often drew women turned sideways to enter through doors, or struggling to fit in carriages. This was deliberate. It allowed women to take up more physical space and make those without these garments work around them – giving them power.

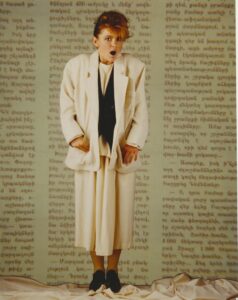

The 1980s power suit shows the same effect. Women reversed features normally used to identify them as different to men. Replicating broad shoulders using shoulder pads let women claim the value given to men with this feature. They gained the stature associated with broad shoulders, belonging to the dominant figure in a room. They still used their clothes to take up and demand space, but now more metaphorically, they used their clothes to take up and demand space in the workplace.

The 1800s saw many dramatic silhouettes yet the 1880s bustle invented a figure, rather than enhance an existing part (such as wider hips). The structure under skirts extended to the back at the waist – making this a focus of the outfit. The bustle used a lot of fabric. Using more fabric to increase the cost was an age-old technique of power.

Bustles also created a train behind, reminding viewers of royalty and political power. I wonder if drawing attention to the back of the outfit had the psychological effect of allowing women to pass in front more, using their assets to their advantage.

Unlike the other two examples, the bustle also gave women greater adaptability and freedom. The bustle was usually collapsible. Once women were at the table (physically or metaphorically) it would not cause any issues or disadvantages. At that point, the rest of the clothing took greater importance. I doubt it’s a coincidence that women’s fashion preferred waistcoats and military-inspired jackets at this time. As with the power shoulders, this used the aspects of male fashion that were valued and appreciated, and applied them to women.

The return of these fashion trends also represents similar values, which questions how distinct new style ideas are. Is this pure coincidence? Did it just happen to be every 100 years? Is it a result of similar events happening at the same time each century, and their lasting results? The 20s supports this – the Napoleonic Empire, the First World War and Covid pandemic. Is this a cycle of how long generational memory lasts or how few new ideas there are?

What other trend loops can you identify? Which of these ideas should I research further?