Most people know 1918 as the first time some women voted in the UK, but women successfully voted in the 1869 election. The suffragists of Manchester led a huge campaign after spotting that the wording of the 1868 Reform Bill was wrong. The wording accidentally enfranchised women who met its other criteria, leading to thousands of women voting.

According to Romilly’s Act (passed in 1850), the term ‘man’ in law referred to both men and women (so murder was illegal for both). By using ‘man’ instead of ‘male persons’. This meant women who met the criteria of the 1868 Reform Bill would have the vote too. MPs pointed out this blunder but did not change it during its discussions in Parliament. The reform aimed to give the vote to upper-middle-class men earning above a certain threshold.

Coverture meant that a woman’s possessions (and herself) belonged to her husband, and so only those with independent wealth could qualify. This still represented 3 to 4,000 single and widowed women. The debate over whether fighting coverture should be before or after obtaining the vote for some women had caused most divisions within the movement to this point. Was it better to have some women voting or women being economically independent and hopefully voting to come later.

Lydia Becker led the Manchester National Society of Women’s Suffrage. She quickly gained a reputation for her organisational efforts and the level of detailed communication she provided to and with other suffrage groups nationally.

Many of the group’s other members were from the Bright Circle – the extended family of Ursula Bright (previously Mellor) and Jacob Bright (a Manchester MP). Between them, the Bright Circle had representatives of almost every strand of campaigns to improve women’s rights – from temperance to early female doctors to the abolition of slavery.

Other members like Josephine Butler filled in the gaps – the more conservative London suffragists regarding the Bright Circle’s involvement in her campaign in defence of sex workers as ‘vulgar’.

The case of Lily Maxwell, a shopowner in Manchester, also inspired the campaign. The spelling of her name (using the masculine form used in Germany), meant she had accidentally added to the register for the 1867 elections. Even thought the 1832 Act (the 1867 Act was not yet in effect) explicitly said ‘male persons’, her vote counted. Newspaper coverage speaks of the cheers of men around her at the hustings. The conservatives did not challenge her vote – a recount was pointless as Jacob Bright won by a landslide.

Many officers laughed women out, or refused to add them. Officers faced punishment for wrongful additions, but not for missing anyone off. Yet, supportive or ambivalent officers added around 230 women. Appeals that failed were then grouped and challenged in court. History was central to the legal arguments, aiming to discredit the idea of women’s exclusion being natural. Early suffragists produced a whole book of examples of this being a modern phenomenon. Despite common belief otherwise, the first time women voting was illegal was in 1832. Many laws still stood that previously allowed women to vote – never overturned

“Ye know me, the said Dame Dorothy Packington, to have chosen, named and appointed my trusty and well-beloved Thomas Lichfield and John Burden, Esquires, to be my burgesses of my said Aylesbury. And whatsoever the said Thomas and George, burgeresses, shall do in the service of the queen’s highness… [I] do ratify and approve to be my own act, as fully and wholly as if I were or might be preset there.”

– Dame Dorothy Packington

In the 1600s, Dame Dorothy Packington chose two MPs to ‘represent her as if in person’. Her agreement qualified without complaint as her power came from her late husband’s estate. This meant it was used by the lawyers in the court case of 1868. Anticipating other arguments against them, the lawyers used the history of women voting in local elections to illustrate the demand and use of female votes.

Despite this, they lost the court case. The rejection of John Stuart Mill’s 1967 suggested amendment of the original bill to replace ‘man’ with ‘person’ supposedly proved giving women the vote was not parliament’s intention. One of the judges explained it was obvious ‘dogs or a horse’ didn’t have a vote without explicitly wording it and women were the same.

However, the course case only represented the appeal cases. Anyone added to registers directly by Overseers, or if a Revising Barrier had accepted their appeal for its merit, kept their vote. Eight women voted for the liberal candidate in Manchester – paraded proudly through the streets on their way. Initial criticism by the conservatives was quickly dropped when Lydia revealed a 9th woman could be persuaded to vote for their candidate.

Lydia herself wrote that she didn’t know how many women had managed to vote nationally. But at least 109 individuals and 11 townships successfully claimed their place on the register. Some of these come from Scotland – where a group had added themselves after a similar realisation.

In their Annual General Meeting, the Manchester society advised rejected women to ‘tender’ their vote (attend elections and state how they had planned to vote). This was an acceptable practice under the appeal system. If women followed this advice, there could be evidence of the voting preferences of thousands of women nationally in 1868. I’d love to one day research this and see what I can find.

These stories undermine the Suffragette myth that nothing really happened before them. This is almost bizarre as one of the key lawyers was Richard Pankhurst – husband of Emmeline and father of Christabel, Adela and Sylvia Pankhurst. It shows the extremity of the refusal to give women the vote – even when caught out in their out rules.

It is really interesting and sad why such an amazing and inspiring story is forgotten. I only heard of it as an offhand comment in a text on other political campaigns in the 1800s.

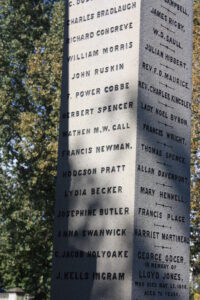

For their work for women’s rights and other campaigns, some of the key members earnt a space for their name on the Reformers Memorial in London.